BIRMINGHAM, A. C. (AP) — Selma’s historic 1965 voting rights march didn’t take place on a single day: Attendees spent 4 nights camping along the roughly 55-mile (89-kilometer) highway through Alabama, sleeping in tents and nearby to cultivate buildings under surveillance to prevent attacks by white supremacists.

Now threatened by decades of weather and attrition, the camps used by those walkers are among the most threatened historic sites in the country, according to a new assessment through a preservation group. The sites, along with 10 other locations in nine states, require immediate attention or are lost, according to the nonprofit National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Three of the camps are personal rural lands across 80 United States, which bind Selma and the capital, and the fourth is the city of St. Jude, a Roman Catholic resort where walkers spent the night before thousands of people followed the Reverend Martin Luther. King Jr. at the Alabama Capitol on March 25, 1965, to demonstrate for black suffrage.

The direction of the walk is different today than it was 56 years ago, what was then a two-lane road is now four-lane, with more traffic and new construction, leaving the main points of preservation to the families who own the camp and local authorities, accepting as true is losing courtesy in the sites and others at a time when the right to vote and racial justice have it’s back to being a national problem.

“These 11 places celebrate the interconnectedness of American culture and recognize it as a multicultural fabric that, once reconstituted, shows our true identity as a people,” said Paul Edmondson, president of the Washington-based organization, which publishes a list of endangered species. . puts each and every year. Other options on the 2021 list include:

– Trujillo Adobe, the remnants of a nearly 160-year-old Latin American agreement in Riverside, California.

– Summit tunnels 6

– Georgia B. Williams Nursing Home in Camilla, Georgia, once the black-owned birthplace for African-American women in the state.

– Boston Harbor Islands, archaeological and ancient on 34 islands off the coast of Boston.

– Morningstar Tabernacle No. 88 Order of Moses Cemetery and Hall, a black historical settlement dating back to the past 1800 in Cabin John, Maryland

– Home of Sarah Elizabeth Ray, a black activist who started a legal war after she was denied access to a separate ferry to Detroit in 1945.

– The Riverside Hotel, which housed black blues and other Jim Crow-era musicians in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

– Pine Grove Elementary School, built for black youth through philanthropist Julius Rosenwald in 1917 in Cumberland, Maryland

– Threatt Gas Station, which welcomed black travelers on Route 66, and the farm relatives circle in Luther, Oklahoma.

– Oljato Trading Post, built in 1921 and one of the few remaining Navajo trading posts in and around San Juan County, Utah.

Selma’s march began two weeks after Alabama state infantrymen beat up protesters seeking to leave Selma on a day called “Bloody Sunday. “The Selma and Camino sites are now part of the Selma National Historic Trail.

Under the supervision of members of the Alabama National Guard, protesters first stopped about 7 miles east of Selma on land owned by David Hall, a black farmer who was in danger of being harassed by disappointed white neighbors during the march. he showed them piled up around a chimney built on an old steel drum to heat, and Hall’s granddaughter, Davine Hall, said visitors stopped.

“Sometimes we faint and there’s a total backyard of bicyclists, other people who have stopped and need to take a walk,” said Hall, who divides his time between the circle of relatives and California. night. “

The next rainy night, they stayed on Rosie Steele’s property, then stayed on land owned by Robert Gardner, where Tuskegee University scholars provided dinner and walkers slept on pool air mattresses, many of which deflated overnight. Gardner’s daughter, Cheryl Gardner Davis, was four years old at the time and still remembers the crowd and the noise.

A white neighbor threatened her father with welcoming the walkers, she said, and for years the circle of relatives remained silent about the experience.

“I don’t forget that my father told us that we couldn’t go anywhere alone, that we had to have an adult with us. He said that if we saw a car on the road, it was the FBI that was watching us, “Davis said. “It was a bit sautomobiley. “

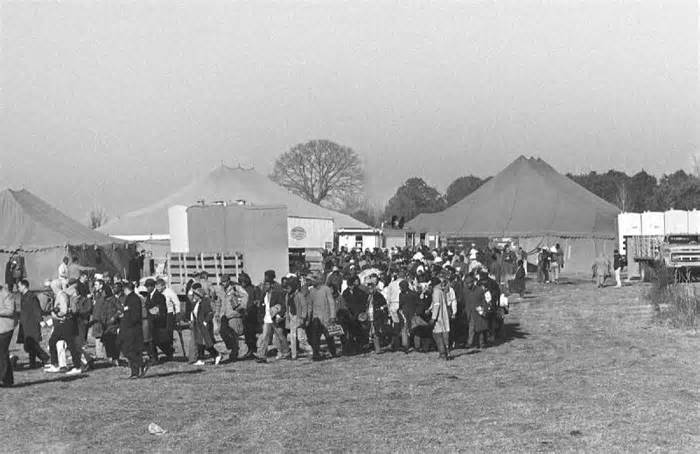

Dozens of walkers spent the night on the road, and their numbers increased exponentially during the time the march reached downtown Montgomery.

While the families that own the camps have had little contact over the decades, plans are being made to maintain the houses that were on the Hall and Gardner sites in 1965 and, in all likelihood, turn them into educational sites, said Phillip Howard, a representative of birmingham’s domain. running on the allocation with the Conservation Fund.

On the last night of the march, about 4. 83 miles from the Alabama Capitol, protesters camped out in the city of St. Jude have been entertained by stars including Harry Belafonte; Tony Bennett Peter, Paul and Mary; Sammy Davis Jr. and Joan Baez before the final leg of the trip. The chapel remained there as long as it was then.

Today, near the Capitol, a historic stone marker recounts the occasions of 1965, when King addressed another 25,000 people at the end of the march. Simple metal panels identify the campsites used by walkers along the way, but there’s not much else to do. they represent its importance.

___

Reeves is a member of AP’s Race and Ethnicity team.

Be the first to comment on "Selma march camps on the most sensitive list of threatened sites"